While 66-0177 gets most of the glory (because

it was the first C-141 into Hanoi),

64-0641, along with numerous others,

participated in the return of American POWS

from Hanoi. It made its trip to Hanoi on

February 18th, 1973, bringing 20 POW's

back to Clark. On February 23rd, 1973, it flew

one POW from CLARK to the US. On

March 14th, it flew another 40 POWS from Hanoi

to Clark and on the 17th

ifo:\141\dotcom\64\pic_64_0641.php

flewo:\141\dotcom\64\pic_64_0641.php

20 POWS from Clark back to the US.

On 20 March, 1975, this aircraft crashed into a mountain range in northwest Washington after being mistakenly cleared to an unsafe altitude. The crew did not notice the air traffic controller's mistake, and 10 crew and 6 passengers were killed.

Returning to home station after a long overseas

mission, 64-0641 was cleared for

an enroute descent. During the descent, the air

traffic controller confused call

signs with another aircraft and cleared the

StarLifter for a descent below

minimum vectoring altitude. The aircraft crashed

into Mt. Constance, with the

loss of 10 crew members and 6 passengers.

At 2300 local time on 20 March, 1975, 40641

approached the stormy coast of Washington at

FL370. The

crew had already had a long duty day, having

flown from Clark to Kadena, then

Yokota, and finally home towards McChord. They

had been up for more than 28

hours. The crew was tired and ready to be home.

Ninety miles from McChord they

were given a descent clearance to 15,000 feet,

and given a frequency change. On

the new frequency, they were given a clearance

to 10,000 feet.

The Seattle Center controller was also

controlling a Navy A-6 (Call sign "Navy V

28323") that was returning to NAS Whidbey, about

60 miles north of McChord. Still

60 miles from McChord, the C-141 reported level

at 10,000. The controller

directed "maintain five thousand". The C-141

responded "five thousand. MAC 40641

is out of ten".

A couple of minutes later, the A-6 pilot

requested further descent. The

controller, confused why the Navy jet hadn't yet

descended, re-cleared him to

5000 feet.

About that time, the controller at Seattle

Approach noticed that he could not

find the C-141 on his radar scope, and contacted

the original controller at

Seattle Center. Repeated radio calls failed to

raise 40641.

No one on the crew of three pilots and three

navigators, including an examiner

navigator had noticed the erroneous descent

clearance below the minimum sector

altitude or the unusually early descent. The

C-141 had impacted the near vertical

northwest face of Mt. Constance, on the east

slope of the Olympic Mountains, 150

feet from the top of the 7743 feet peak.

There were no survivors.

This information was provided by Paul Hansen

I have a little bit more to add about this

story...

Mike Novack

This is my perspective on this accident and

'flying tired' in general. If anyone

else has a different view I'd love to post it

here.

At the time of the KTCM accident in the Olympics

I was assigned to McChord in the

8th MAS, the squadron to which these crew

members were assigned. CINCMAC then had

a decidedly SAC view of the world and decided

that we should be operating in a

hard-crew mode -- that is, a crew would be

comprised of a pilot, co-pilot, nav,

engineer[s] and loadmaster who flew together as

a crew whenever possible. I think

this was in response to the string of earlier

accidents involving controlled

flight into terrain. He evidently had the idea

that if people knew each other

better they'd be less likely to crash an

airplane. (As a side note, there were

lots of off-color jokes about hard-crews

floating around; idle minds are

fertile ground for this sort of thing.)

Prior to the hard-crew concept being

implemented, crew scheduling was basically

this: look on the list of crew-members and

assemble one .. based on who was

around at the time. It was a mix-and-match"

approach made of interchangeable

parts like a model A Ford was made when mass

production really took off. This

had worked for years, and I always viewed it as

a testament to "standardization",

consistent training practices, and checklists

that it worked as well as it did.

However, as crew members we didn't know what to

think about the new concept as

most of us had never experienced anything like

it. It was not a desparation move,

but probably a rational attempt to address a

problem that seemed to have no other

immediate solution (other than TCAS, which was

years away). Many hours of

discussion about it ensued. My personal feeling,

and those of many others, was

that it could lead to dangerous shortcuts and

expectations about what someone

you knew well would do, as opposed to doing it

per the book, the same way

every time.

The crew that crashed in the Olympics was my

assigned hard-crew. I had flown

with them a few times as a crew in the months

prior to this accident. As anyone

whoever worked as a flight crew scheduler knew

would be the case, vacations,

medical care, training, personal emergencies,

etc., meant that no hard-crew

would actually ever fly as a complete unit very

often in the real world. In this

case, fortunately for me, I was unable to make

the trip due to some dental work

and was DNIF when my crew left McChord about 10

days earlier on this ill-fated

trip.

You may not have heard about the big incident

that happened after the crash but

those of us who were there will never forget it

(or at least a version of it).

This is mine:

The day after the accident the commander of the

22nd AF from Travis was at McChord.

All all the crew members who were not away from

the base on a trip or leave were ordered to

show up at the base

theater. He briefly stated what was known about

the accident. He read us the riot

act about what crappy pilots and navigators we

must be. When he asked if there

were any questions someone stood up in the

audience and asked him if he was aware

of the duty day the crew had just experienced,

which as noted in the accident

summary above, was about 28 hours. From his

initial recounting of the story it

did not appear that he was at all aware of this

aspect of the crash. The general

exploded into a fit of rage, saying "You can't

tell me we can't fly at night

without running into terrain!" He was getting

pretty hot. The deputy wing

commander, who was on stage with the general and

the wing commander, tried to

calm everyone down by saying, quite

respectfully, words to the effect of

"General, I think you may have misunderstood the

question". He proceeded to

recount what they new about the crew's duty day

at that point, finishing with

"they must have been very tired".

Then a very bad thing happened: Just about

everybody in the audience exploded into applause

and even some cheering.

From there, it went down hill ... fast. The

general glared at the wing commander and the

deputy wing commander, and anyone else on stage,

said the "briefing" was over,

and stomped out.

The Wing Commander, who was left in the

general's wake

turbulence standing on the stage, took over. He

told us all "That was the most

disgusting display of professional ethics I have

ever seen." Then he stomped out,

the deputy wing commander tight on his heels.

For all of us peons it was quite a sight to see

generals and colonels behaving so

badly...we thought this only happened in the

movies.

The meeting in the theather happened on a

Friday, the day after the crash.

I'm sure there was a lot that transpired in the

Wing Commander's office in the hour after that

assembly at the theater, but of course none of

us knew about any of that. All we

knew was that by Monday, the deputy wing

commander was gone. He was banished to

Minot ... and a couple of years later was

assigned to the embassy in Tehran,

where he was taken hostage (1979) and eventually

came back a hero.

About 3 or 4 days after the crash I was off DNIF

status and flying again. As we

flew out on a trip to Elmendorf, heading over

the Olympic Mountains

from McChord towards Neah Bay, more or

less the exact reverse of the route of the plane

that crashed, we could still

hear the ELT beacon from that aircraft on guard

channel (we had to turn it off

until we were out of range). These were our

friends. It was not a good way to

start our trip.

A year or so later I upgraded to A/C, and year

or so after that was scheduled to

participate in one of the big exercises in

Europe. I had been working a straight

8-5 shift in the office all week. As usual, our

departure time was 0300 or some

equally ridiculous hour and I had great

difficulty getting any decent sleep during the

day before the trip, and was alerted and

reported for duty at about 1 am. I

already felt like crap at that point. We were

supposed to fly to Goose Bay or

somewhere up there, wait on the ground for a

couple of hours and then proceed on

to Europe. I looked at the flight plan.

I don't recall my flight training ever including

a section on philosophy, but I

had developed one of my own. Of course, you

always looked at fuel, weather,

alternates, NOTAMS, etc. But my "flight planning

philosophy" also included trying

to determine what condition I expected myself

and the crew, (and especially the

pilots), to be in at the final destination, in

this case about 16 hours from our

initial departure. I did some quick math .. by

the time we were scheduled to be

in Europe I would have been up, as would most of

the rest of the crew, except

maybe the loadmaster, for about 24-30 hours

without any decent sleep. We were not

an augmented crew.

I talked to the nav and co-pilot and asked them

what they thought. I made a

decision and when I checked in at the command

post at McChord before heading out to the

plane I told the duty controller, "I'm going to

take the flight to our

intermediate stop, but when we get there, we

will be too tired to proceed safely

on the final leg of this trip, so I'm going to

declare crew rest in the interest

of flying safety when we get to our first stop."

Not being a big-picture sort of

guy (or maybe just stupid), I thought I was

doing them a favor. They would have

about 6 hours to plan for it.

He went nuts and called my squadron commander at

2 am and handed me the phone.

He, in turn, asked me "What the hell are you

thinking? You can't possibly know

how you'll feel 7 hours from now." "Yes I can",

I responded. "I've only been

doing this for 5 years but I know EXCATLY how

I'll feel! Seven hours more tired

than I do now. With the prospect of another 7

hour flight across the NAT tracks

into the sunrise, and into European airspace."

He told me to keep my mouth shut

until we got there, THEN declare crew rest. He'd

save his real chewing out for

later.

So, as directed, about 1 hour out, having

already been up about 16 hours, even

though our official duty time was then only

about 6 or 7 hours, I called the

command post and told them of my decision. I

don't know if they have been given a

heads up or not, but they said OK, a fresh crew

was staged and would pick up

the plane. We went into crew rest.

Shortly after I arrived at the BOQ, I got a call

from some colonel at 21st AF HQ

who said I had pissed him off, and "if you don't

want to fly in 21st airspace,

that's just fine. You won't!". I was a Captain

.. he was a full bird .. so I

didn't argue.

We were effectively grounded, though they would

not actually say that. They

punished us by putting us on a continuous alert

for about 2 days, and finally had

a west-bound crew pick us up and deadhead us

home. The crew that picked us up was

a McChord reserve crew..they seemed to know all

about this whole thing and said

it was "the talk of the system". We stopped at

Scott to drop somebody off and

were then to proceed home to McChord.

A MAC HQ Flight Examiner jumped on, and told me

to get in the pilot's seat. I was

about to get a "no-notice" flight evaluation. I

passed. After the flight

evaluation debriefing was completed back at

McChord, he asked me about what

happened. I told him. He said that I had done

the right thing.

So what exactly was the message to a young A/C

here? I never could figure it out

then, and to this day, about 30 years later,

still don't know. Over the brief six

years I flew C-141's, I flew too tired too many

times to remember. Once, flying

between Clark and Guam I woke up in the pilot's

seat and looked around the

cockpit. EVERYONE else was snoozing. We were not

at war with anybody then. To me,

it seemed like a very stupid thing to risk lives

of crew and passengers

needlessly when the solution was simple: get

some decent crew rest if you can

figure out how. If that meant having to declare

crew rest in the interest of

flying safety, so be it. I only did it once (and

the consequences are detailed

above), but I don't think it happened often

enough.

With the modifications to the C-141 that came in

later years, (in-flight

refueling) and the pressures of several wars, I

am quite sure that this problem

only became worse. Perhaps the adrenalin (or

maybe 'go-pills') that comes with a

"cause" (like a war, or med-evac flight, or

humanitarian relief) compensates in

some small way. Flying a load of empty pallets

back stateside did not seem like a

worthy enough cause to take the risk.

Mike Novack

Saturday, November 27 2004 (07:19 AM): I

received this additional information

from Les Crosby:

I was in the Air Force from 1968 to 1976

stationed at McChord AFB, Washington.

64-0641 had been there two years prior to my

arrival. I worked on the flightline

my entire time and worked on almost every C-141

assigned to the base and quite a

few transiting through going overseas, either

going to Viet Nam, Japan or

Germany. I enjoyed working on the C-141's (even

the hangar queens).

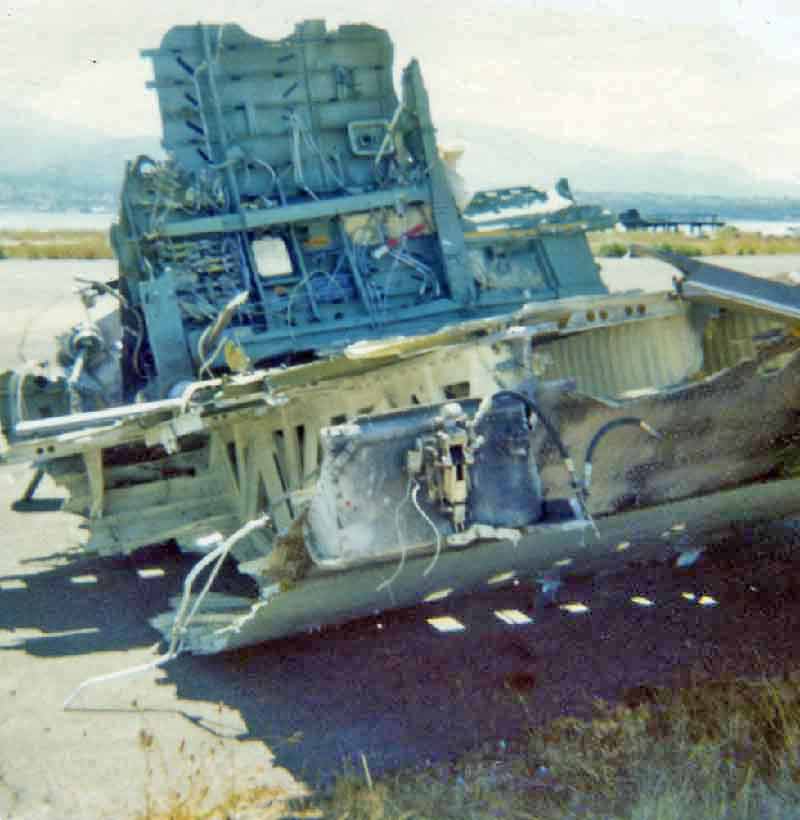

Here are some pictures of the recovered wreckage

of 64-0641. Ironically, I and a

group of other mechanics took off all the

leading edge panels on the left wing so

the wiring for the crash position indicator

could be replaced just prior to its

last flight. The crash wreckage was taken to the

Coast Guard station at Port

Angeles, Washington. One of my friends was part

of the recovery team and I went

up there and took the pictures in May 1975. You

have my permission to use the

pictures on your website. I know it's sad to see

40641 this way and the loss of

the 13 people on board but it's part of the

history of the C-141.

As a side note 64-0641 participated return of

our prisoners from Hanoi. At the

time I took the pictures you could still see

remnants of the Red Cross on the

tail.

Saturday, December 31, 2005 04:00 pm: I received these comments from Al Hurst, a former simulator instructor at KTCM:

I really appreciate the effort you have gone to

in memorializing a great

airplane. Thank you a lot.

I read Mike Novack's account of 40641 and would

like to add a few comments of my

own.

I had intended to ride home on 641 that night. I

was close to retirement (an

euphemism for getting rid of the Christmas

help), and thus was grounded in

January of 1975. As a simulator instructor

pilot, I still had "jump" orders so I

took one last sort of nostalgic trip to the

Pacific.

Our crew and that of 641 had identical frags:

KTCM to KHIK, crew rest, then to

RPMK for a 24 hour crew rest, then to RJTY and

home. I planned to jump ship in

Yokota and talked with the A/C of 641 shortly

after they blocked in at Clark. No

problem, they said, so that was the plan.

Our crew rest at Clark was terrible. We arrived

about 1800 hours local and tried

to manage our sleep schedule. We talked it over

and decided to stay up as late as

possible so as to extend out sleeping into the

daytime. Didn't work. By 2200 the

last guy had faded and was fast asleep. We awoke

about 0700, had breakfast at the

club (me with the examiner navigator who died in

641 - good friend of mine), then

hit the BX. The usual stuff.

Early in the afternoon we all tried to sleep,

but with the heat and noise it was

impossible. Finally we were alerted and set sail

for Yokota. Nearing Yokota, the

A/C said how tired he was already and what it

would be like 11 or so hours later.

Everyone agreed that crew rest in the interest

of flying safety was the best

option.

The duty officer was not amused. After some

discussion during which our A/C

remained steadfast with the decision, the duty

officer leaned forward and said

something to the effect of: "Captain, you are

making a big mistake!"

The A/C said: "Sir, if I make a mistake it is

because my judgment is impaired by

fatigue."

So, we took 15, I got my shopping done (which

was the real reason for the trip,

truth to tell), and decided not to wait for 641.

Our trip home was uneventful.

Approaching McChord, I was in the jump seat when

we were cleared from 14,000 to

10,000. We discussed it and agreed that 10 was

safe since the highest peak was

Mount Olympus at a shade under 8,000. Although I

don't remember any of the rest

of the flight, for some reason, that passage

stuck with me with great clarity,

probably because of what happened to 641. What

great events or non-events hang by

such slender threads.

Al Hurst

Bryan McPhee, a former C-141 navigator,

submitted a copy of an MAC Flyer magazine

article from October of 1977. The topic was a

fatigue study being performed (this

one using C-5 crews) and it promised that the

results would be published when

they were available. As of 1/24/2006, all we

have is the initial article.

If anyone has a copy of the results of the

study, that would be a great addition

to this 'teaser' article. They suggested it

might be published in the January or

Feburary 1978 issue.

This note was sent in by Ray Romero in September

2006.

To this day I still believe that I was in some

way remotely involved with the

events that happened that fateful day.

I was onboard Navy C-1A BuNo. 146041 preparing

to land at King County Airport in

Seattle.

For us Non-Navy Types:Here's what a C-1A looks

like

Our pilot kept asking control if that call was

for him, as you will notice the

similarities in call numbers. To this day I am

certain that not only we were

confused by that similarity but the crew of 0641

as well.

I remember later on in the evening at home

listening to the news about the crash

of the Starlifter in the Olympics. Further

reports at the Air Station in Whidbey

Island confirmed my nagging suspicions that it

was the aircraft that was airborne

at the same time we were in that vicinity.

Warm regards,

Ray Romero

Mangaf, Kuwait

This note was sent in by Al Brewer on March 1,

2007:

Reflections on the Crew Duty Day

The MATS system in the piston engine and turbo

prop days is different from the

MAC system transited with turbine power. There

are far fewer legs that demand the

extended crew duty day. But to provide the

flexibility to be able to operate

throughout the world with political constraints,

weather, or other factors

requiring extended duty days, the entire system

must be trained to accommodate

such methodology. This would require routine

extended duty day missions. The crew

managers must design crews with the proper

experience. The crews must be prepared

to cope. The aircraft commanders must not be

chastised when calling a halt

whenever the crew's capability is exceeded. The

intense "on time departure"

pressure prevalent within the command can

compromise this responsibility.

Operating extended duty days just to be

operating extended duty days is ill

advised. For the purpose of training the system

to be able to do so is logical;

for the purpose of extending airframe

utilization rates when faced with airframe

shortages in a contingency is a HQ AMC decision

with which the system should be

able to cope.

MATS had accidents. Aircraft ditched, aircraft

were flown into the terrain,

aircraft stalled, spun, and crashed. Most of

these were the result of the

equipment involved which was far less capable

than the interim modernization

aircraft (C-130 and C-135) or the modern turbine

aircraft. The usual crew duty

day for the crews operating these earlier

aircraft was the extended crew duty

day. I do not recall the crew duty day as being

listed as a causatory factor in

these accidents. The longer crew duty day,

twenty-seven hours from the time the

crew reported for duty, was routine and

accepted.

The airlift system can be managed to conserve

the number of crews utilized, to

conserve the number of airframes utilized, to

expedite the crew cycle through the

system, even to reduce cargo hold time in the

aerial ports. In the time frame of

the McChord accident, the driving factor was a

lack of airframes to meet

requirements. Relatively, there were plenty of

aircrews. With airframes as the

driving factor, the airlift system was managed

to cycle airframes through the

system as quickly as possible. The tools to do

this are staging the crews to keep

the aircraft moving and to utilize extended crew

duty days to eliminate enroute

stops.

These parameters shift from time to time. In

1977 the driving factor had become

the crew. The C-141 system shifted to more crews

keeping their airplanes as they

transited the system. On occasion an airframe

type would be managed differently

within the system. The C-133 from about 1966 on

was managed with the crews

keeping their airplanes to increase mission

reliability. The C-5 was so managed

at times.

I believe there are sound reasons to operate

some extended duty day missions in a

peacetime environment. Add to that the

requirement to practice the contingency

mission somewhere in the system and even areas

normally operating only "peacetime

missions" may have to stretch. In view of the

historical ability to operate

extended crew duty days and thus increase

utilization and deliver greater

capability, the senior leadership of the command

would be in an untenable

position if the airlift capability that could

have been delivered were not.

The crew force, their managers, the support

system, all must be capable of

operating using an extended crew duty day. The

brunt of the load as usual is on

the crew.

Al Brewer

I never thought of the long days as a "training

experience" but I suppose Al

makes a good point ... you have to flex the

whole system to see where it breaks.

It was never explained to me (or any other crew

member that I knew) that way when

I was flying the line back in the mid-70's.

However, it seems like you could "practice"

staying awake while sitting on a bar

stool. They could have given "check rides" and

if you fell off (I have many

times) you'd only fall a few feet instead of

crashing into a mountain! Of course,

then you'd get busted and have to "practice"

some more.

Mike Novack

This article made possible by: The State of

Washington Washington State

Department of Archeology and Historic

Preservation You can see the original page

at

this link

HistoryLink File #8562

U.S. Air Force C-141A Starlifter crashes into

Mount Constance, on the Olympic

Peninsula, killing 16 servicemen, on March 20,

1975.

On the night of March 20, 1975, a U.S. Air Force

C-141A Starlifter, returning to

McChord Air Force Base from the Philippines via

Japan with 16 servicemen aboard,

is flying southbound over the Olympic Mountains.

A Federal Aviation

Administration air traffic controller, nearing

the end of his shift, mistakes the

Starlifter for a northbound Navy A-6 Intruder,

on approach to Whidby Island Naval

Air Station, and directs the pilot to drop

altitude to 5,000 feet. Complying with

the incorrect order, the C-141A crashes into

Warrior Peak on the northwest face

of Inner Mount Constance in the Olympic National

Park, killing all onboard.

Attempts are made to recover victims, but due to

inclement weather and dangerous

snow conditions, 15 of them will not be

recovered until springtime. In terms of

loss of life, it is the biggest tragedy ever to

occur in the Olympic Mountains.

The Aircraft

The Lockheed C-141A Starlifter was introduced in

1963 to replace slower

propeller-driven cargo planes such as the

Douglas-C-124A Globemaster II. It was

the first jet specifically designed for the

military as a strategic, all-purpose

transport aircraft. The Starlifter, a large

aircraft, 145 feet long with a

160-foot wingspan, was powered by four Pratt &

Whitney jet engines. Its

shoulder-mounted wings and rear clamshell-type

loading doors gave easy access to

an unobstructed cargo hold, measuring nine feet

high, 10 feet wide and 70 feet

long.

At a cruising speed of 566 m.p.h., the plane was

capable of carrying more than 30

tons of cargo approximately 2,170 miles without

refueling. When configured for

passengers, the C-141A could accommodate 138

passengers.

On Thursday, March 20, 1975, U. S. Air Force

C-141A, No. 64-0641, under the

command of First Lieutenant Earl R. Evans, 62nd

Airlift Wing, was returning to

McChord Air Force Base (AFB) from Clark AFB,

Philippines, with en route stops at

Kadena Air Base, Okinawa, and Yokota Air Base,

Japan. The plane was due to arrive

at McChord at 11:15 p.m. Flown by the Air Force

Military Airlift Command (MAC),

Starlifters normally carried a six-man crew

consisting of two pilots, two flight

engineers, one navigator, and one loadmaster.

But on March 20, because of a

grueling, 20-hour flight from the Philippine

Islands, the C-141A was carrying

four extra relief crew members. In addition, the

plane was transporting six U.S.

Navy sailors as passengers, heading to new ship

assignments.

The Mishap

At 10:45 p.m., while over the Olympic Peninsula,

approximately 90 miles from

McChord AFB, the Federal Aviation

Administration's (FAA) Seattle Air Traffic

Control (ATC) Center gave the pilot clearance to

descend from Flight Level 370 to

15,000 feet. Several minutes later, approach

control at Seattle Center cleared

the plane to descend to 10,000 feet.

The last radio message was received at

approximately 11:00 p.m. when the pilot

acknowledged authorization from approach control

to descend to 5,000 feet. Five

minutes later, the C-141A disappeared from the

radar screen.

Attempts to Search and Rescue

Besides being nighttime, weather conditions in

the Puget Sound area were extreme,

with high winds, snow, freezing rain, a low

cloud cover, and a only a

quarter-mile visibility. McChord immediately put

rescue helicopters and an Air

Force Disaster Preparedness Team on alert,

awaiting break in the weather. Coast

Guard Air Station, Port Angeles, became

base-of-operations for the impending

search-and-rescue effort. Shortly after the

plane's disappearance, some 120

mountaineers from the Seattle, Everett, Tacoma,

and Olympic Mountain Rescue Units

and several military helicopters assembled

there, awaiting orders.

At 2:45 a.m. on Friday, an Air Force Lockheed

C-130 Hercules from McClellan AFB,

California, flying at 30,000 feet, reported a

rough "fix" on the Starlifter's

crash-locator beacon, in the mountains

approximately 12 miles southwest of

Quilcene in Jefferson County. Ground parties

were flown by helicopter to

Quilcene, prepared to hike to the crash site,

but they needed the location

pinpointed because of the rugged terrain and

winter weather. Lieutenant Robert

Herold, a helicopter pilot from Coast Guard Air

Station, Port Angeles,

established the exact location of the signal by

triangulation several hours

before weather allowed the wreckage to be

spotted from the air. It had crashed

into the northwest face of Mount Constance

(7,756 feet), just inside the eastern

border of Olympic National Park.

Bad weather continued to plague aerial search

operations throughout Friday.

Finally, at about 4:20 p.m., after searching

sporadically for eight hours, an

Army Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopter from Fort

Lewis spotted the wreckage. The

pilot, Warrant Officer Edward G. Cleves, and his

observer, U.S. Forest Service

Ranger Kenneth White, reported the plane

appeared to have impacted at about the

6,000-foot level of jagged Warrior Peak (7,310

feet), then slid down the

mountainside. They reported seeing the tail

section, a large piece of the

fuselage and part of a wing at the 5,000-foot

level in a canyon above Home Lake,

the headwaters of the Dungeness River, and

debris scattered over a wide area on

the steep slope. The helicopter made three

passes over the area, but neither

Cleves nor White spotted any bodies or signs of

life. Because there were deep

fractures in the snow above the wreckage, White

reckoned an avalanche would soon

bury the crash site until spring.

On Saturday morning there was a break in the

weather. Army helicopters dropped

explosive charges at various locations on the

steep slopes surrounding the

wreckage to diminish the avalanche hazard. Then,

two Army Boeing-Vertol CH-47

Chinook helicopters ferried several rescue teams

onto the mountain to search the

ridges and ravines for possible survivors. They

were also hoping to find the

aircraft's flight data recorder, which might

provide clues to the cause of the

crash, but much of the wreckage and debris had

already been covered by snowfall.

Forced out by a new storm, the searchers left

the site that afternoon without

finding any bodies on the mountainside.

On Sunday and Monday, poor flying conditions in

the Olympics hampered efforts to

search the Mount Constance crash site for

survivors and the flight data recorder.

Mountain-rescue experts conceded, however, there

was no doubt all 16 persons

aboard the Starlifter were dead.

A Regrettable Human Error

Meanwhile, at McChord AFB, an investigations

board, consisting of eight Air Force

officers and four National Transportation Safety

Board (NTSB) officials, headed

by Major General Ralph Saunders, was convened to

determine the official cause of

the tragedy. Of particular interest were radio

communications between the C-141A

and Seattle Center, minutes before the crash.

On Monday morning, March 24, the FAA announced

that a "regrettable human error"

by a Seattle Center air traffic controller was

believed responsible for the loss

of the Starlifter. Tape recordings of the radio

transmissions revealed that the

controller had confused the southbound Air Force

C-141A with a northbound Navy

A-6 Intruder that had been flying at the same

altitude, en route from Pendleton,

Oregon, to Whidby Island Naval Air Station. The

controller intended to instruct

"Navy 28323" to descend from 10,000 feet to

5,000 feet, but inadvertently gave

the order to "MAC 40641," flying over the

Olympic Mountains. The Starlifter's

pilot responded: "Five thousand -- four zero six

four one is out of 10." Still

approximately 60 miles northwest of McChord AFB,

the pilot started to descend and

struck a ridge near the top of Mount Constance.

The error was discovered when the

tapes were played, an hour after Starlifter had

gone missing. The controller, in

a state-of-shock, was relieved of his duties and

placed under a doctor's care.

Finding the First Body

Meanwhile, a 10-man search team from Olympic

Mountain Rescue (OMR) and the

National Park Service, airlifted to the crash

site, discovered the forward

fuselage section and the remains of Lieutenant

Colonel Richard B. Thornton, the

aircraft's navigator, while searching at about

7,000 feet, well above the

suspected impact level. Late in the afternoon,

David W. Sicks, team leader and

OMR's chairman, decided to abandon a further

search of the area as deteriorating

weather threatened their air support. The

searchers spent the night at a base

camp they had established earlier at the

5,000-foot level.

On Tuesday, March 25, the morning was clear but

the temperature was 10 degrees

Fahrenheit and there was a strong 20-knot wind

blowing. Snow conditions were

becoming unstable, cornices were building, and

there was an avalanche nearby.

Rescuers recovered the body from a stash site

and then were flown from the

mountain by helicopter just as visibility began

to drop. Although the team was

prepared to stay for two days, Sicks estimated

it would have taken that long to

make the 10-mile trek on winter trails under

impossible weather conditions to

reach the Dungeness River Road, the only safe

exit route.

On Tuesday afternoon, over 800 persons gathered

at the McChord base theater for

two separate memorial services held to honor the

10 airmen and six sailors who

perished in the Starlifter accident.

Difficult Conditions

In addition to the volatile spring weather,

there had been two minor avalanches

at the crash site while the Olympic Mountain

Rescue team was there. Olympic

National Park's Chief Ranger, Gordon Boyd, said:

"It is extremely steep,

hazardous terrain, not only because of avalanche

dangers, but because of ice and

rotten rock" (Seattle Post-Intelligencer). Due

to the risk involved, the Air

Force postponed further efforts at recovery

until after the spring thaw. Boyd

said park rangers would monitor conditions

around Mount Constance and advise the

Air Force when it was safe to allow search

parties back into the area. Snow on

the mountain was reported to be over 15 feet

deep and unstable.

On Friday, May 16, 1975, Captain Douglas

McLarty, McChord AFB Public Information

Officer, announced that, due to above-average

spring temperatures, the wreckage

of the Starlifter was beginning to emerge from

the snow. A team of two Air Force

pararescue specialists and two Olympic National

Park Service rangers had been

camping on Mount Constance, at the 5,000-foot

level, monitoring snow conditions

and protecting the integrity of the crash site

from interlopers. While there, the

men found the body of Airman First Class Robert

D. Gaskin, the first since March

24. And on May 29, the team discovered the

remains to two more victims, whose

bodies were airlifted to McChord AFB for

identification.

Finding More Bodies

On Monday, June 2, the official probe into the

Starlifter crash was finally

officially reopened. Teams of Air Force crash

investigators and pararescue

climbers were airlifted into the area and set up

a base camp at the 5,500-foot

level of Mount Constance. The following day,

search teams, probing the snow with

10-foot rods, found five more bodies before high

winds and a snow storm forced

the temporary shutdown of recovery operations.

Although unpredictable spring weather and

occasional avalanches continued to

hamper recovery efforts, the investigators and

search teams made steady progress.

The Starlifter's cockpit and a section of the

fuselage, containing several

bodies, had been sighted in a snow-filled

crevasse approximately 400 feet below

the crest of Warrior Peak. The elusive flight

data recorder was recovered late

Thursday, June 12, and sent to the NTSB in

Washington D.C. for evaluation.

On Monday, June 16, Major General Ralph

Saunders, commander of the Aerospace

Rescue and Recovery Service and president of the

investigations board, announced

the Air Force had concluded its investigation

into the crash of the Starlifter.

The last two bodies had been found and removed

from the crash site over the

weekend and all the victims were accounted for.

Over the next several days, Air Force personnel,

Olympic Mountain Rescue members

and Forest Service and National Park Service

rangers set about the daunting task

of cleaning up the crash site. Army CH-47

Chinook helicopters lifted the large

pieces of the aircraft from mountainside, while

smaller pieces of debris were

collected in cargo nets and flown out. The

wreckage was airlifted to the Coast

Guard Air Station in Port Angeles and then

trucked to McChord AFB for further

study and disposal.

Bad Luck, Fatigue, and Inexperience

Although it was clear that the Starlifter's

collision with Mount Constance was

the direct result of an incorrect order from the

FAA air traffic controller,

critics believed other factors could have

contributed to the tragedy, including

bad luck. Had the aircraft been on a slightly

different course or 500 feet

higher, it would have missed Mount Constance,

the third highest peak in the

Olympic Mountain Range. Air Force C-141As were

equipped with radar altimeters

that should alert the crew when the aircraft

falls below a "minimum descent

altitude." However, bad weather, particularly

snow, could have rendered the

equipment useless.

Crew fatigue was also believed to be a factor

contributing to the accident.

Although augmented with an extra pilot and

navigator, the crew was at the end of

a grueling 20-hour day and became complacent,

choosing not to challenge the air

traffic controller's direction to descend to

5,000 feet while flying over a range

of mountains. En route Low-Altitude Flight

Charts, which the pilot uses while

flying IFR (instrument flight rules) don't show

terrain heights, but the

navigator has access to Tactical Pilotage Charts

that do. The pilot should have

followed MAC procedures and checked the terrain

before accepting the instruction.

The Starlifter's flight crew, although

qualified, was supposedly inexperienced,

having fewer than the 1,500 hours of flight time

the Air Force considered to be a

desirable minimum. As part of Defense Department

budget cuts, the Air Force

Military Airlift Command had furloughed 25

percent of its most experienced C-141

pilots since January 1975. Forty-four

experienced C-141 pilots (18 per cent),

assigned to McChord's 62nd Airlift Wing, had

been removed from flight status. As

a result, the younger and less-experienced

pilots and crew were overworked and

under-trained.

In terms of loss of life, the crash of the Air

Force C-141A Starlifter remains

the biggest tragedy ever to occur in the Olympic

Mountains.

U. S. Air Force Casualties:

Arensman, Harold D., 25, Second Lieutenant,

Irving Texas (copilot)

Arnold, Peter J., 25, Staff Sergeant, Rochester,

New York (loadmaster)

Burns, Ralph W., Jr., 42, Lieutenant Colonel,

Aiken, South Carolina (navigator)

Campton, James R., 45, Technical Sergeant,

Aberdeen, South Dakota (flight

engineer)

Evans, Earl R., 28, First Lieutenant, Houston,

Texas (commander/pilot)

Eve, Frank A.,, 27, Captain, Dallas, Texas

(copilot)

Gaskin, Robert D., 21, Airman First Class,

Fremont, Nebraska (loadmaster)

Thornton, Richard B., 40, Lieutenant Colonel,

Sherman, Texas (navigator)

McGarry, Robert G., 37, Master Sergeant,

Shrewsbury, Missouri (flight engineer)

Lee, Stanley Y., 25, First Lieutenant, Oakland,

California (navigator)

U. S. Navy Casualties:

Dickson, Donald R., Seaman, Tempe, Arizona (USS

Dubuque)

Eves, John, Third Class Petty Officer,

Ridgewood, New Jersey (USS Dubuque)

Fleming, Samuel E., Chief Warrant Officer,

Alameda, California (USS Coral Sea)

Howard, Terry Wayne, Third Class Petty Officer,

Sylmar, California (USS Dubuque)

Raymond, William M., First Class Petty Officer,

Seattle, Washington (USS Coral

Sea)

Uptegrove, Edwin Wayne, 35, Lieutenant,

Coupeville, Washington (USS Coral Sea)

Sources:

| David Gero | Military Aviation Disasters: Significant Loses Since 1908 | (Sparkford, England: Patrick Stephens, Ltd., 1999), | 116; |

|

Al Watts

Wayne Jacobi S. L. Sanger |

No Sign of Life at Scene | Seattle Post-Intelligencer, | March 22, 1975, p. A-1; |

|

Jack Wilkins

Wayne Jacobi |

Storm Halts Search at AF Plane Crash Site | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | March 23, 1975, p. A-3; |

| Martin Works | Weather Slows Crash Search | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | March 24, 1975, p. A-3; |

| Al Watts | Death of a Jet | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | March 25, 1975, p. A-1; |

| Al Watts | C141 Flight Crew's Actions Probed | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | March 26, 1975, p. A-3; |

| Wayne Jacobi | Body of Crash Victim Found | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | March 26, 1975, p. A-3; |

| Al Watts | Jet Missed Clearing Peak by Less Than 500 Feet | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | March 27, 1975, p. A-8; |

| Weary Crew May Have Partly Caused Fatal AF Jet Crash | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | March 28, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Al Watts | Crew of Crashed Plane 'Weary, Inexperienced' | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | March 29, 1975, p. A-3; |

| Dick Clever | Did Air-Pressure Rule Affect Doomed Crew? | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | March 30, 1975, p. A-1; |

| C-141 Wreckage Beginning to Emerge | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | May 17, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Two More Air Crash Bodies Recovered | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | May 30, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Crash Investigators Set Up Base Camp | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | June 3, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Weather Shuts Down Crash Investigation | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | June 4, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| C-141 Crash Victim Identified | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | June 5, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Wayne Jacobi | Hazards Plague Body Removal | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | June 11, 1975, p. A-3; |

| Flight recorder Recovered from Fatal Crash Site | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | June 13, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Air Force Concludes Probe of C-141 Crash | Seattle Post-Intelligencer | June 17, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Svein Gilje | McChord Plane, 16 Aboard, Crashes | The Seattle Times | Tuesday, March 21, 1975, p. A-1; |

| Svein Gilje | No Survivors in C-141 Plane Crash | The Seattle Times | March 22, 1975, p. A-1; |

| Plane Occupants Identified | The Seattle Times | March 22, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Weather Halts Recovery of Plane Victims | The Seattle Times | March 23, 1975, p. A-7; | |

| Wrong Orders May Have Doomed Jet | The Seattle Times | March 24, 1975, p. A-1; | |

| John Wilson | Fatal Message: Maintain 5,000 | The Seattle Times | March 25, 1975, p. A-7; |

| Body found at Site of Air Crash | The Seattle Times | March 26, 1975, p. A-4; | |

| Svein Gilje | General's Remarks on Jet Crash Stir Furor at McChord | The Seattle Times | March 28, 1975, p. A-1; |

| Colonel Rumored 'Fired' in Clash Over Jet Crew's Rest | The Seattle Times | March 28, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Flight Recorder Found At Last | The Seattle Times | June 13, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| Probe of Air Crash Finished | The Seattle Times | June 17, 1975, p. A-3; | |

| ASN Aircraft Accident Description Lockheed C-141A-20-LM Starlifter 64-0641 Seattle, WA | Aviation Safety Network website accessed December 2007 (http://aviation-safety.net/database); | ||

| Accident Details: March 20, 1975 | Planecrashinfo.com website accessed December 2007 | ||

| (http://planecrashinfo.com/1975/1975-18.htm). |

This image (by "Animal" [ Kevin Koski ] )

was found on a web site devoted to mountain

climbing in the great

Pacific Northwest (

Cascade Climbers

).

The folks lurking around that site know some of

the Olympic

Mtn Rescue folks who were involved in the

recovery operations. The tall peak on

the far right (Warrior Peak) was been renamed

C-141 Peak in honor of the crew.

According to some comments left on

the site, ."The plane however went into the side

of Pyramid peak,

which is at the upper left of the big headwall

with the snowfinger

going to its middle base.

The recovery team went to the base of Pyramid by

going up the long snowfinger

and then up the finger to the left."