StarLifter

The C-141, Lockheed's High Speed Flying Truck

by Harold H. Martin

IN THE BRIEFING ROOM at Charleston waiting for his crew to arrive, the lean, hawk-faced captain talked about his future. Soon, he said, he was getting out of the Air Force. He wasn't angry. He wasn't bitter. He just didn't feel he was improving himself professionally. He was thirty-one. He had two sons to educate. He knew now what it was to fly a big jet to airfields all over the world as an aircraft commander, and he knew that he handled this job with the high skill of a professional. That was one trouble, perhaps. The challenge, the excitement of learning, had gone out of it. But the burden of it, the long hours of droning flight, the responsibility for making the block times, for keeping the planes moving, grew more onerous every year. The airplane was nice enough to fly. It would almost land itself. Or take off with no hands. It had an amazing ability to fix itself when some little thing went wrong. The engineers called it the "Lockheed fix." Maybe that was part of the trouble. It was a good plane. But the life it generated for those who flew it was not so good. In trying to get everything out of the airplane they possibly could-"they" meaning MAC headquarters-they got too much out of the man. So he was leaving. To get a job teaching at some little college out West, perhaps, and a house with seven or eight acres of space around it. He was born in the East, in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, but now he felt the East closing in on him. A new section of the country, a new job, a new beginning, a new challenge. Maybe then he could get over the feeling that for a long time he had been, as he put it, just peeing upwind.

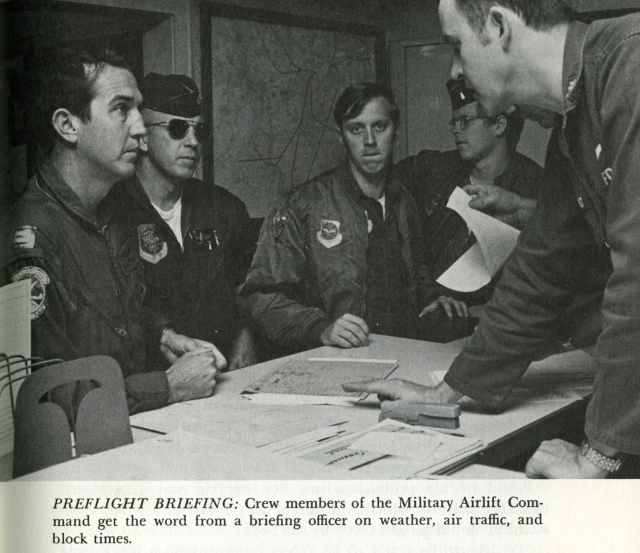

The captain's mood of disenchantment had no effect upon his sharp professionalism. The crew, strangers all, came in- the tall blond copilot; the chubby navigator, tucking a calorie counter in the leg pocket of his flight suit; the flight engineer, a master sergeant with the dark, heavy face of an Indian; the blond scanner, a tech sergeant, carrying a paperback on whose cover two women writhed in passionate embrace. One loadmaster was an old-timer, a master sergeant, the other a curly-haired, baby-faced airman.

Each, as he entered the crew lounge, went immediately to the rack where the technical manuals were kept that contained every recent change in operating procedures that might affect his job. Keeping his own tech manual up to date was of first importance, as evidenced by a bit of doggerel seen on bulletin boards throughout the system.

When my mortal shell is ghosted And by Heaven or Hell I'm hosted, To be wined or dined or roasted, Let them praise me when I'm toasted: "Though little can be boasted, His books were always posted."

The AC's briefing was brisk, brief-and by the book. He told them our destination, which was Elmendorf by way of Dover, and the load, out of Dover, would be 44,705 pounds of mixed cargo, including forty-six boxes containing 828 pints of whole blood. Gross weight of the airplane with 130,000 pounds of fuel would be 314,000 pounds, which was two tons under the limit allowed. Now, would each man examine the crew manifest to see that his name and serial number were correct? Did anyone want his family notified as the plane landed or departed each station?

>

>

This is a special service, useful when there is sickness at home or a baby is expected. Normally a wife can know where her husband is at any given moment by calling a special number at ACP. A tape recording will tell her where his crew is at the moment, whether inbound or outbound. On Christmas and New Year's the wing commander himself may cut the tape and add a little message of appreciation and thanks to those whose husbands are away. (Formerly, wives could call ACP and ask the duty officer personally for a husband's whereabouts. Some husbands forbade this. They felt that such a call might imply that a wife wanted to make very sure that her spouse would not come home unexpectedly.)

"Any appointments to be broken?" the AC asked. "Any personal equipment missing?" (Each man carried his own helmet and oxygen mask.)

"Standard procedures throughout the mission," the AC said. "If there is any deviation I'll tell you before I deviate. If, while we are flying, I do anything you don't understand, by all means bring it up. Maybe I am doing something wrong."

He called for the normal check list, communications, gear-yanking and flap-lifting duties from the copilot, plus making him custodian of the coffee fund. He named the big sergeant with the Indian look his NCOIC-the noncom in charge for the mission. He asked the navigator to make sure that every man's serial number was on the per diem form ("Next," said the navigator, "they'll be asking navigators to take over the chaplain's duties") and he warned the loadmasters about handling the blood pallet with special care.

"All hands stay on headset till we start engines, so I'll know you are all fired up and ready to go. Above 25,000 feet, make sure you have oxygen always available. If you have to move away from your regular source, take a portable bottle with you. I've been aboard one of these things once when it depressurized and I can tell you it's serious. A lot of physical damage can be done to a man in a hurry. So get your mask on quick, then help the next guy if he needs it."

Proud of his professionalism, the captain was determined that this mission, which well might be his last as a MAC commander, should go off exactly by the book.

"I'd like to be ready to go thirty minutes before block time at each station along the route. But especially here. This is the most hectic departure. This is the one we must not miss. Any questions?"

Two hours later, in the left-hand seat of a T-tail with engines idling, the captain watches as the sweep second hand on his watch moves around to 17:45. Then with one smooth, steady motion he shoves the throttles forward and the droop-winged StarLifter, so awkward on the ground, lumbers with a banshee screech down the taxiway, and turns at the head of the runway for a last quick line-up check. Then, as if flung from a catapult, it is lifting off and climbing, up through cloud and down through cloud, to the onload point at Dover.

Soon, now heavy laden, it is up again, climbing through the busiest skies on earth. Planes flash by above us and beneath us and all the sky to the north and east is etched with their vapor trails. Before we are well on our way eight separate ground controllers have guided us through the traffic, and each as we leave his area wishes us a polite "good evening." We fly through a long twilight, chasing the dying sun. Forward in the cockpit three heads show in silhouette moving nervously right and left, up and down, as the pilot, the copilot, with the scanner in the jump seat between them, watch for the wandering bug-smasher, the small private plane the ground radars might have missed.

We top out, finally, at 35,000, still in daylight though the earth below is dark. Everybody seems to relax a little. The scanner leaves the jump seat and goes back to the seat in the corner beyond the navigator's desk, where he buries himself in his paperback book. There is no work for a navigator as the plane travels these controlled airways, so he studies his calorie chart, and notes, mournfully, that of the TV dinner the load-master is now heating for him, he can eat only a sliver of meat. The loadmaster comes up with coffee. At the engine panel, the big sergeant leans back in his chair, watching the gauges. All seems well. The Eeper-the engine pressure ratio-is holding steady at 16, the exhaust gas temperatures range from 390 to 400, well within tolerances; the slow turbines are turning at 84 percent of their rated 6796 rpm, and the high-speed compressor is whirling at 82 percent of its top 9655. The fuel flow in pounds per hour ranges from 3300 on No. 1 engine to 3500 on No. 4. The master gauge shows 101,000 pounds still left. We are 29,000 pounds lighter than when we left the ground.

The engineer swivels his chair toward the crew bunk seat, ready to talk. He's forty years old, a big, heavy-faced man, and he's been in the Air Force for twenty-two years, seventeen of them on flying status. Two years ago he had had to make a decision. He was thirty-eight years old. He could take his pension and go out at twenty, and still have two years to find a job on the outside before he turned forty. And maybe he should have done it. But with five kids in school, and a wife who didn't really mind his traveling, he figured it would be best to stay on for thirty. Maybe, if he kept his nose clean, he could make chief master sergeant. That was the trouble, though. Things could go the other way. You could blow twenty years in a hurry. One little screw-up could wreck a man's whole career. There was a sign in a latrine somewhere out on the line that he remembered. It said, "To err is human. To forgive is not MAC policy."

The blond engineer said he had the same choice to make, and he'd made it the other way already. He was thirty-three, with sixteen years in. When he finishes his twenty, he'll still be only thirty-seven. So he will take his retirement and go. He'll start a little flying service somewhere, in Louisiana, or maybe in Newfoundland. His wife is a Newfie and she likes it up there. He spent a month's furlough there, and it was great hunting and fishing country that was just coming into its own as a tourist spot. A flying service taking hunters and fishermen into the back lands would make a lot of money.

The blond young loadmaster came up from the cabin, bring* ing more coffee. "What about you, Load? When are you getting out?" the engineer said.

"Tomorrow if they'd let me. I've already got my lines out. I'm putting in for a loadmaster's job with a commercial airline."

"On the commercial airlines the loadmasters wear miniskirts," the engineer said. "You ain't got the build for it."

"Not them cargo outfits, they don't," the youngster said. "With the big planes coming in, that's the part of flying that's going to boom. The freight. It's going to be like the railroads in the early days. I've got two years to go on a four-year hitch, and I'll get out right in the middle of it. They will be hollering for somebody who knows how to move that freight."

At ten o'clock it is still light. We are flying at 35,000 feet in clouds and rain. The AC is at the controls. The copilot is asleep, his headphones on, his oxygen mask dangling ready at his chest. The navigator is alert now, watching his radar for weather ahead. We are getting a little ice, but hot air, bleeding off the engines at 760 degrees, is circulating through the wings' leading edges and the engine nacelles to keep it under control. The two load-masters, one flight engineer, and the copilot are all asleep. The AC looks around and grins. "You know the old saying-'Flying the line is hour after hour of utter boredom, interspersed with moments of sheer terror.' "

The deep darkness falls. The copilot stirs, stretches, yawns, and scratches. When he is well awake, he takes over the controls. The AC slides into the right-hand seat and quickly goes to sleep. It is a short night. At 2:30 the great snow peaks of the Canadian Rockies gleam below us in the early light. Ahead, under a cover of cloud, lies Whitehorse, in the Yukon. The plane begins to stir with the rituals of landing.

"Behold, a miracle," the navigator says. "They've got us on radar."

"We've lucked out again," the loadmaster says.

Voices on the radio take over, giving us altitudes and headings. Out of a sky that was hard and clear and blue and very smooth we drop down through bumpy cloud, the plane shivering like a frightened horse. The little tensions, light but noticeable, that go with every landing, begin to build up on the flight deck. The pilots, in crisp, noncommittal voices, read off the check lists. The engineer checks his fuel gauges and passes up the TOLD sheet-takeoff and landing data-which tells the pilot what speed he must maintain to keep the plane flying at its landing weight. Then many things begin to happen in ordered sequence. The gear goes down with a rumble, the flaps with a grinding roar. Soon the nose lifts in the flare-out, the wheels screech on the runway, the spoilers open, and the thrust reversers come on like a kick in the chest, slowing the plane to its taxi speed. Ahead of us in the smoky morning the lights on the guide jeep wink their "Follow me."

"Now," said the AC, "if we don't hit a moose, we've got it made."

A crew on which three men out of six are leaving the service in various stages of disenchantment is not typical of all MAC crews, but it is far from rare. On every mission there is at least one flight crewman who yearns for the day when he can turn in his baggy green ramp pajamas for a civilian suit. Some are just fed up with flying. "I want to work at a desk from nine to five," a bachelor lieutenant said. "I want to sleep in the same bed every night for a change-with the same woman. I don't want to spend another Christmas Eve staring out over the ocean from Drifters Reef at Wake Island." (On all the major holidays-Christmas, New Year's, Thanksgiving-all the bachelors are flying the line as the harassed scheduling officers juggle their rosters to keep the family men at home.) Many look with longing at the higher pay and shorter flying hours the civilian airlines offer. A grizzled lieutenant colonel making $15,000 a year as a MAC aircraft commander, flying 100 to 125 hours a month, knows that his civilian counterpart is flying eighty hours and earning twice to three times that. The pay scale, for example, for a Pan American pilot with ten years' experience, flying as captain on a 747, is $49,875 a year.

Many feel that they have advanced in rank as far as they can go. A staff sergeant said: "We've got too many people for the slots. I've got twenty-three years in-good reports all the way. But the chance I'll move up from master to chief in the next seven years is practically nil." Most noncoms, of course, would settle for a master sergeant's stripes. A staff sergeant said, "I've got in eleven years, and if I don't make tech by the time I hit twelve, they can shove it. I've got my house and car paid for, and the GI Bill will support me while I learn a civilian trade."

Many feel that even if they advance steadily in rank and grade, they will basically be doing the same thing, year after year, as long as they stay in. A pilot can advance from aircraft commander to pilot-instructor to flight examiner, but the difference is not great. Whether he's a first lieutenant or a bird colonel, the man in the left-hand seat is pushing the same buttons, flying by the same book. A Travis navigator said: "We are increasingly caught up in a computerized, mechanized, and sanitized flight operation. It is highly effective in terms of what it gets done-but it is terribly ineffective in terms of human satisfaction. Somehow we've got to feel again that what we are doing is worthwhile."

Part of the crew's restlessness stems from the fact that many men feel a deep need to test themselves in a freer, more competitive environment. "I still need to know whether or not I can hack it on the outside," a newly promoted major said.

Knowing that every time he flies the line he leaves an unhappy wife at home gnaws at the conscience of many a MAC crewman. A captain said: "I've got a nervous dog and a nervous wife.

When I'm gone he barks all night, and she sits there with a pistol." A sergeant said: "My old lady tells me she'd rather I'd be gone six months and home six months, instead of this constant 'hello, good-by; hello, good-by.' " A jealous wife can be even more troubling. She has heard disturbing rumors of the strange spell the Japanese girls can cast upon a man, of the charm of the Filipinas, and the frauleins, and even more disconcerting, of the wit and the gaiety of the perky hostesses who fly the civilian contract planes on the same routes the StarLifters fly. It is hard to convince her that her flying spouse does not spend his off time in wild revelry with these, and she cannot be persuaded that on nine missions out of ten all he ever sees of some exotic port of call is the runway, the ramp, the billets, and the snack bar. So? Then why is that sign over the bar in Yokota: "Soon you must leave your loved ones and return to your dependents?" That, he replies weakly, applies only to base personnel.

It is the little and seemingly trivial things that often push a man to the final decision that he wants out. "We come out in overdrive, eager to keep moving," a Charleston major said. "But the people out on the line aren't always geared up to move quite that fast. So, you get in at three A.M. and they leave you waiting on the ramp an hour, freezing your tail because somebody forgot to alert the crew bus." Crews in stage must sleep when they can, and billets that are too hot, or too cold, or too noisy in the daytime, irk them sorely. Torrejon, Spain, is a good crew rest base. The little Spanish maids who clean the rooms would not think of rattling a doorknob when the "Occupied" card is in its slot-but they will stand outside in the hall and chatter in voices that murder sleep. Snack-bar food can be a misery. There is a standing jest in MAC that once a crew member's grease level falls below a certain point, he must have a hamburger or he will go into convulsions. By this criterion, the best hamburgers are from the snack bar at Clark AFB in the Philippines, which is known throughout MAC as "The Greasiest Spoon in the West." At Clark, where the transient crews are billeted in trailers, the houseboys do not gather in the halls and chatter. But they do move with quiet stealth by night to pilfer small articles from crew baggage, and it is highly unwise to leave a wallet on a dresser. "They didn't leave me enough to by a monkey-pod toothpick," moaned an airman who awoke to find his shopping money gone. At Elmendorf, crews arriving at odd hours dehydrated and athirst find nothing open where they can have a relaxing drink before taking their rest, which is known as 2-time. "Hell hath no fury like a MAC crewman who can't find a bar open at four o'clock in the morning," observed an amiable colonel out of Travis.

>

>

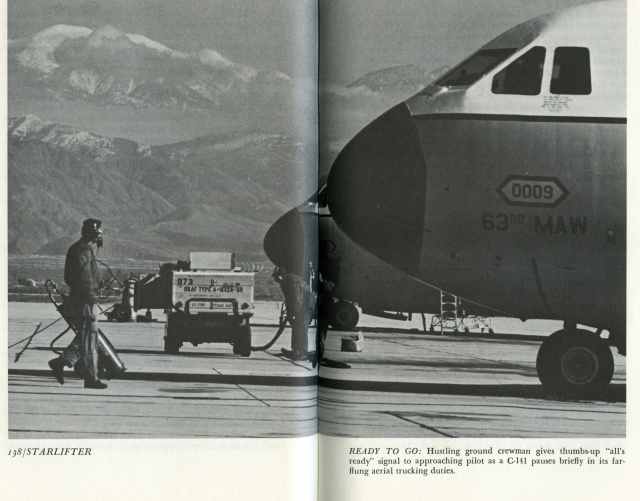

Bar hours that ignore the needs of wayfarers are about the only complaint the crewmen file against the huge operation at Elmendorf, jump-off point for the NorPac flights. In winter, Hercules aircraft of the 54th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron seed the air above the fog-shrouded runways with dry ice as the StarLifters approach, dispelling the ice crystals and clearing a hole through which the big planes safely land. On the ground, the 602nd Support Squadron boasts that its Quick Stop-Fast Fly Service is the most effective in the Pacific. The MAC crews do not strongly dispute this. As a service stop, Elmendorf is superb. Two hours out, each incoming AC must radio in what maintenance his plane will need. The specialists who will fix it are waiting at the parking ramp as it pulls in. From the Fleet Service crew that loads on the food and water, and cleans the latrines, to the mechs and electricians and hydraulic experts who make the quick fixes on the engines and the flight systems, to the Ramp Tramp, who keeps an eye on all of them, the Elmendorf operation is fast, efficient, and friendly. Nine hundred planes a month put in here, making it the second busiest port in the Pacific. Eight hundred of them are StarLifters, with a maintenance reliability record of 97.6 percent. Rolled onto hardstands like racers into a pit stop, they are fixed, refueled at 900 gallons a minute, and sent on their way in less than ninety minutes. (Once in a test, Elmendorf moved a Combat Pacer plane in twenty-two minutes.) Eight out of ten of them depart on time.

A base that works as smoothly as this is a blessing to a staging crew. It is a comfort to an aircraft commander who, when he calls ACP for a WAG-a WAG being, in MAC-ese, a Wild Ass Guess-as to when he may be leaving, gets instead a fixed block time. This means his crew is off the hook. They will not have to wait around for hours beyond their normal twelve-hour rest, then take off tired when a plane comes into service just before time to rest again.

The 602nd claims that its excellent record for getting planes in through the weather and out on time is the result of the talent and dedication of its maintenance crews. The 610th at Yokota, which handles a thousand planes a month, at a similar maintenance reliability rate, snorts derisively at this theory. The reason so many planes leave Elmendorf on time, Yokota argues, is that crews in their eagerness to get out of there will take anything that has wings on it. For, leaving Elmendorf, they are either headed for home-or for Yokota, and the happiest crew rest in the Pacific.Voices in the Night

OUT OF ELMENDORF, the route of the StarLifters lies west and south over the great bulge of the North Pacific to Yokota in Japan. In the long daylight of the sub-Arctic summer, or the twenty-hour dark of the winter nights, the heavily-laden planes climb seven miles above the earth before they level off in the thin cold air high above the weather. Below, under a layer of cloud that is always there, lies the 1200-mile chain of the Aleutians, black volcanic islands whose peaks thrust 9000 feet above the slate-gray sea. The names of these bleak rocks ring in the memory like leaden bells-Adak, Shemya, Attu-old way stations and by-passed battlefields of the now half-forgotten war with Japan. For nine hours the big cargo-lifters race the sun, their journeys beginning usually in the twilight of an Alaskan evening and ending at dawn at the huge air base south of Tokyo, which is the hub of our airlift operations in the Far East. The hours of darkness are brief, spent as the plane slides down the long curve of the Kuriles-Russia's islands, with unfamiliar names like Paramushir and Shaskotan and Matua and Rasshua. There are strange voices, too, speaking in these dark skies-the voices of the Soviet controllers at radio stations on the outlying islands, and sometimes their traffic is so heavy that it is difficult to make contact with our own check points. For all their electronic aids, navigators sweat as they fly this route, watching their computers, taking their long-range fixes, training their radars on the island land masses to the north, shooting the stars with a sextant in the age-old way to cross-check their electronic guidance systems. At one point along this leg of the journey, Russian turf is only 180 miles away-and though it has not happened yet, lurking in the

back of every navigator's mind is the worry that he might come too close and look out in the dark to see a Soviet patrol plane, wagging its wings and blinking its lights in the international message, "Follow me."

Nobody was concerned with this possibility as, in a summer twilight, a Dover bird, flown by a Dover crew, sped down the Aleutian chain from Elmendorf, bound for Yokota with a load of airplane engines consigned to Cam Ranh Bay. They had other, more immediate concerns. No one aboard had been in-country (into Vietnam) in the current month and time was running out. They were also inhibited by the presence of a stern and professorial major who rode the copilot's seat and, in his role of flight examiner, asked sharp and searching questions of the harassed young captain riding as aircraft commander. The young officer answered as best he could, but as the Black Hatter pressed him harder, he began to grope for the answers, finally withdrawing into himself with the dry grin of a treed possum. It was obvious that he was unhappy. It was equally obvious that the major was not pleased, so there was no banter, no friendly give-and-take as the plane climbed out and leveled off at its cruise altitude of 37,000 feet. The usual sense of relief and relaxation did not come. The atmosphere remained tense and silent.

Then, suddenly, the mood changed.

The navigator came on the intercom. He had been doing a little figuring, he said. And if his computations were not in error, and if the winds blew as predicted, and if all these T-tails that were coming at us out of the sunset passed safely by-this plane should put down at Yokota about 4:30 the next morning, which was the last day of the month. Then, if the gods remained benign, and the ACP at Yokota did not goof off in some unforeseen manner, it was highly likely that as they finished their twelve-hour crew rest and became legal again, a plane would be ready and waiting to take them in-country-which means into the Vietnam combat zone-early on the following evening. And if their luck still held, the five-hour flight to Vietnam would see them landing at Tan Son Nhut or Da Nang or Cam Ranh Bay, not long before midnight, thus safely beating the end-of-the-month deadline.146/STARLIFTER

they served filets of Kobe beef from young steers that themselves had been massaged vigorously every day, to make them tender and distribute their fat.

The navigator said that Kobe beef was good all right, but the best chow in the Pacific was the Mongolian barbecue they served at the Koza Palace Tea House in Kadena, a restaurant that sat on a hilltop overlooking the old Okinawa battlefields, or in that club at Clark, in the Philippines, that is up in the hills. He went on to describe the Mongolian barbecue. You start with a big bowl, he said, and put in it a handful each of bean sprouts, celery, and chopped onion. Then over this you pour a little scoopful-about two tablespoonsful maybe-of sesame oil, soy sauce, sake, garlic sauce, ginger water, and sugar water. To this you add a teaspoonful of pepper sauce, which is the closest thing to the molten flames of hell this side of the nearest volcano. Then on top of all this you spread thin slices of raw beef, pork, chicken, lamb, and liver. Then you hand it to the cook, who is waiting with a long-handled spatula at the ready, at a flat metal sheet which has been brought to a fierce heat over a charcoal fire. He takes your bowl and dumps it upside down on the hot metal and there is a fierce hissing and sizzling, and smoke billows up, and the pungent aroma of garlic, soy sauce, rice wine and ginger fills the room like some rich incense. Shoveling fiercely, the cook attacks the mound with his spatula, nipping it over, shuffling it, raking it together and flipping it over again, bringing the heat evenly to each ingredient. In two minutes it is done and you sit down and eat it with chopsticks and a bottle of Japanese beer, which is the worst beer in the world but this doesn't matter because Mongolian barbecue is the best food in the world,

From food the talk drifted to souvenirs and the best places to buy them. Every MAC crewman who is married has his house done in MAC Modern, which means he has sent home rattan furniture from Japan, lugging it, oftimes, piece by piece. He has monkey-pod trays from the Philippines, beautifully carved wooden screens from New Delhi, camel saddles from Pakistan, huge wooden knives and forks that hang on walls from Spain, and beer steins from Germany. On his floors are rugs from Turkey and sheep skins from Australia. And he drapes his wife with nielo, the black silver from Bangkok, and pearls and silks from Japan, and leather goods from Italy, and topazes from India, and beggar's beads from Turkey. He buys for himself and his friends Japanese cameras and Seiko watches in Okinawa, for they are cheaper there, and he has suit bags made of heavy blue nylon with his name and rank embroidered on them in white silk.

The major said that the things he liked best were the water-colors, and the beautifully printed books and paintings and flower arrangements that are sold so cheaply in Japan. Somebody, in the dark, muttered that by now he was beginning to believe that the major and the Japanese lady did spend their time arranging flowers and drinking tea.

It was deep night now, remindful of the rueful jest that MAC stands for "Midnight Air Corps-when the sun goes down the gear comes up." There were hard white stars above and milky cloud below, and every half-hour or so the blinking lights of another T-tail shone in the dark, headed east at 39,000 feet. For this is the route assigned to the StarLifters-far to the north to keep out of the way of the faster contract jets. Far ahead the long-range radar on the tip of Hokkaido watched to see that the plane didn't stray too far north and into danger. On the radar the navigator watched the little glowing blips that represented the Kuriles. On one of them, called Shima Shira Tuo, a Soviet radar would be tracking the StarLifter as it passed, "painting" it on his radar while it painted him at the same time. In fact, such a station can be used as a navigation aid-by getting a fix on it, and on Hokkaido, a StarLifter can by triangulation get a rough estimate of its own location.

For the East Coast crews who fly the NorPac route after resting at Elmendorf, this flight to Yokota is merely long and dull-a nine-hour drone. For the West Coast planes that come this way when there is stormy weather in the mid-Pacific, it is a fifteen-hour grind, broken only by a quick stop for fuel at Elmendorf, that puts them into Japan bleary-eyed and weary. A delay at Elmendorf may mean that their crew-duty day will run beyond the permissible sixteen hours before they touch down at Yokota. In this case, the AC may call a crew rest at Elmendorf, but this is rarely done, for beautiful downtown Anchorage lacks charm and Elmendorf, for all its efficiency, is not a place where crews are inclined to linger. The pattern is to request special permission to fly the extra hours-which higher authority is always glad to grant. The urge to press on is less marked when the crew has the opportunity to spend a few extra hours in such pleasant spas as Yokota, Kadena, or Hickam, and planes have a curious affinity for developing in these places mysterious maladies which even the resident Lockheed technician cannot quickly diagnose.

This is difficult to arrange on the rugged StarLifter, a plane whose nature it is to forgive all but the grossest mishandling, and is ready to go more than 95 percent of the time. To keep a Star-Lifter crew on the ground for a little extra rest and recreation, therefore, it is sometimes necessary to enlist the unwitting aid of the Department of Agriculture inspectors, whose job it is to keep plant diseases and insect pests out of the United States. A crew, for example, cannot take a plane out of Yokota on which Asiatic crickets have been discovered, for it surely would be grounded for fumigation at Elmendorf or Hickam. If no crickets are readily available, mice will do. The discovery of a mouse aboard a plane arriving at Hickam from Southeast Asia will mean that the doors must be shut, traps set, and the plane sealed for twenty-four hours. The crew that was supposed to take it out will thus have another day to savor the joys of Hotel Street in Honolulu, or feel the soft winds of Waikiki. Actually, the mouse need not be there in person. A matchbox full of mouse droppings, scattered where the inspector will be sure to see them, will serve just as well.

Conversation is the best antidote to boredom on these long flights and MAC crewmen talk, as old-time sailors used to make scrimshaw, merely to have something to do. Much of the talk naturally has to do with girls, and the places around the circuit where they may be seen in all their varied glories. The whirling, stamping, hand-clapping flamenco dancers of Madrid are vividly remembered, but no more so than the ladies of the Nipa Club, in the Philippines, who perform curious acrobatics before an audience that sits in bleachers, as if watching a wrestling match at the high-school gym. Halfway across the world the dusty city of Adana, Turkey, is recalled, less for its ancient Roman bridge, where camel caravans still dispute the right of way with limousines, than for its area known as The Compound. Here, in a dead-end street of a dozen or more low two-story houses, sad-eyed Turkish prostitutes, obese and grimy, lounge glumly on plush velvet divans behind barred windows that open on the dusty street. There at all hours of the day and night prospective clients peer in at them with the appraising look of cattle buyers. Turkish police stand guard at the gates, collecting knives, pistols, and cameras from those who wish to enter. This trace of official sanction has given birth to a romantic legend, which the young airmen repeat as gospel-the doleful-looking ladies are not truly harlots, but dutiful and loving wives and daughters whom the government has graciously permitted to sell their bodies to pay off debts owed by their fathers and husbands.

The talk drifts on, to a comparison of those towns that are happy places in which to crew-rest, and those that aren't. The Eastern crews like Rhein Main, and Frankfurt, and Madrid, and Toledo, where bullfights are held on Sunday afternoon and the great walled castle on the hill looks exactly like the El Greco painting. On the West Coast, the crews from Norton and Mc-Chord remember the Australia-New Zealand run, a pleasant break from endlessly flying into Southeast Asia. The run goes south from Hawaii, with a fuel stop at Pago Pago in American Samoa, and from there to Christchurch in New Zealand to offload cargo for McMurdo in Antarctica. In the short Antarctic summer the McChord ships go on to McMurdo, but usually from Christchurch the plane goes on to Sydney and a twenty-four-hour crew rest, in a pleasant hotel called the Gazebo. Then on to a lonely little place called Alice Springs, in the heart of Australia, where there is some sort of global communications relay point and there are opals to be bought. And from there all the way across the great desert, to a place called Learmouth on the Indian Ocean, where the Aussies are building a naval base. A van comes out with food here, but that is all the help the crew receives. Here the AC is on his own, with no support of any kind. He locates the airstrip as in the early days of flight. He swoops in low to take a look at the windsock to see which way the wind is blowing and then he pulls up and goes around again and comes back to land. It is a trip on which the plane has to stand up, for there is nobody there to fix it if it breaks down. From Learmouth the plane goes back, 3700 miles across Australia and the Tasman Sea to Christchurch and the most pleasant crew rest of the journey. Sydney is fine, but the people there during three wars have seen too many American troops on rest and recreation leave, and their affection is not boundless. The New Zealanders, though, have stoutly refused to let themselves be contaminated by visitors on R&R, and the town is still unspoiled. The people there are warmly friendly, and their prices for essentials such as beer and taxi fares, restore some of its old power to the American dollar. They tell the small MAC contingent there-100-odd men hardly noticed among Christchurch's 170,-000 people-"We like you Yanks, but not in droves."

Whatever the virtues of Christchurch versus Toledo, crews from the West Coast and the East Coast both agree that for those seeking either to purchase souvenirs or to succumb to the temptations of the flesh, Bangkok is a city that stands apart. A night on the town there has been known to leave a man in a sort of cataleptic trance, a condition known in MAC as DNIF, meaning Definitely Not Interested in Flying. A navigator recalls a young copilot in this condition who forgot that in Thailand an electric razor cannot be used without a transformer to step down the current. "He plugged it in and stood there looking at it while it went to pieces in his hand. Then he brushed his teeth with Brylcreem and got back in bed."

Dawn came over a Japan hidden beneath thick cloud as the StarLifter began the approach to Yokota. Soon in the pilot's earphones could be heard the most comforting of all sounds-the voice of the ground controller, reporting "on course ... on glide path ... on course ... on glide path ... on course. . . . You now have the runway in sight. Take over visually. . . ."