Copyright © - William W Sierra

On St. Patrick's Day, 1973 this aircraft was involved in an incident at McGuire.

Details below, provided by MSgt Edward "Mad Dog" J. Loftus (Retired)

(MADDOGWRI@aol.com).

We were returning from Saigon on 9+ day trip, and we had some problems enroute.

By the time we landed at Dover, unloaded, and refueled we had to accept a crew

duty time extension. We were tired and accepted.

When we called for weather at Mcguire (KWRI) we given temp and winds that

indicated no problems.

But after we had begun the approach we were told that the ground conditions had

dropped to 400 feet and 1/2 mile we continued the approach.

At approximately 120 feet we could not see the runway lights, the windshield

looked like a sheet of frosted glass every time the strobes lite up.

At approximately 110 feet we did not have the runway, so I called for go around

we climbed not knowing that we had clipped the trees.

After we landing, from the opposite end runway, a crew chief came into the

Flight

deck and asked me where we got the trees.

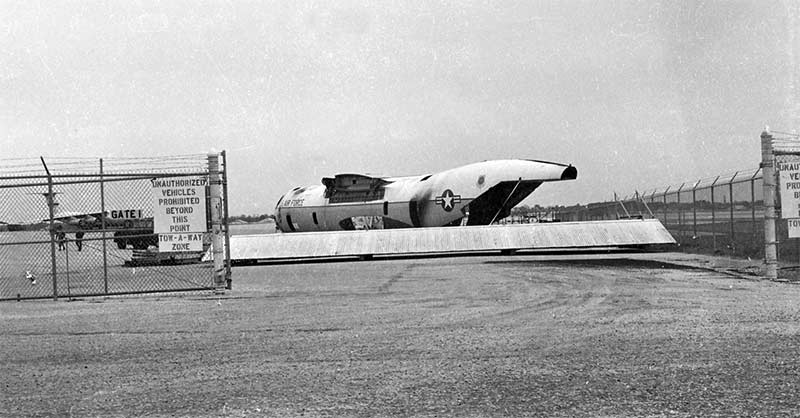

A copy of an official US Air Force photo

The Aircraft is C141A 64-0647, the incident took place on St Patrick's day 1973

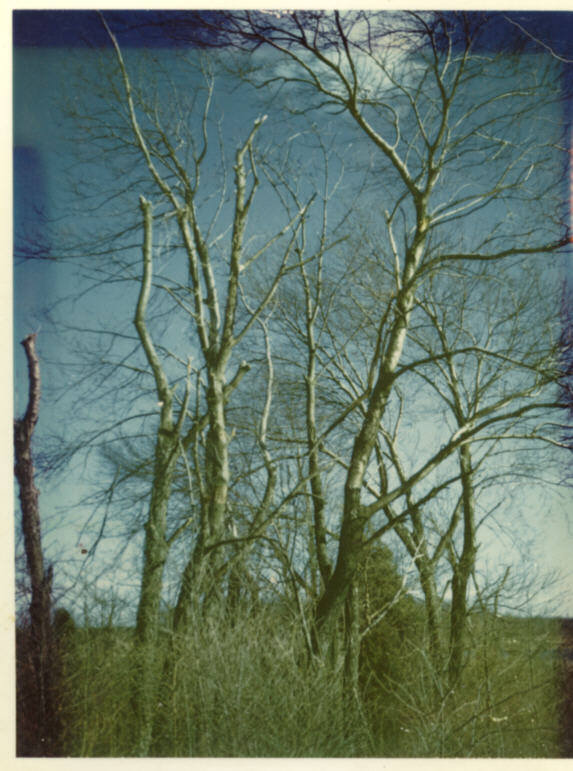

Below are photo's I took later that day after I went home I got a Polaroid and

some film.

This is a shot towards the runway/path of flight it shows the lights mounted on

telephone poles with a steel cross section, At the time the trees I estimated to

be between 30 and 35 feet in height, the top of the strobes I estimated to be

about 15 to 18 feet, in #1 just below the light bar is the Strobe. I think the

distance to this light post was about 2500 feet

This is at the trees we clipped, They would be at the third section of lights

visible in photo # 1

This is perpendicular to the flight path and shows the trees clipped at the top

I estimate the distance from the wing tip to the ground at less than 25 feet as

we were banking trying to slip right an align with the strobes, which from the

flight deck appeared right of windshield

Keep in mind this is from memory 29 years later, I thought I had a copy of my

statement made at the time, but I am unable to find it now.

On 3/24/05 I got the following additional comments from Bill Verno about the 'low approach' described above.

I was the adjacent Crew Chief on 0019 on that particular night.

I spotted the right wing tip of the aircraft as it taxied into position. As she

turned to enter the spot, I could clearly make out a tree imbedded in her

leading

edge and draped over the top of the right wing. I was, to say the least,

astounded at the site .............. to the degree that I questioned what I saw

myself!!!

At it was dark and the taxi and landing lights were on, it more or less blinded

the marshaling Crew Chief's view of the wing. The left wing spotter had no

knowledge as the tree was not in his field of vision. As we started to chock and

pin her, I ran up to 647's Crew Chief and informed him he was in for a busy

night!

After looking at the unbelievable site, he bounded up the crew ladder and into

the cockpit to find out what had happened to "His Plane" ...... I can't be

certain, but I was under the impression that the A/C was a Colonel on this

night.

647 was towed into a hanger bay later on that night and was the talk of the

flight line the following morning!!!

Sgt Bill Verno 438 OMS 1971-1975

Added, December 2008 - From John Attebury:

Having lived through this experience, it is certainly indelibly printed in

my

memory. From the very first, facts began to unfold and make me realize how

close

we had all come to a devastating accident. As an example, no one on the

ground

or in the air had known we even contacted trees for the next two hours

following

a

missed approach, holding and another approach to a landing on the opposite

runway.

We were returning from a trip to South East Asia and approached McGuire,

AFB,

early on St. Patrick's Day, March 17th 1973. We had crew rested at

Elmendorf and

taken an en route diversion to Dover AFB to pick up some helicopter parts

and a

deadheading C-141 crew. I remember on Monday after the accident, the

aircraft

commander of that crew which had been riding in the rear of the aircraft

saw me

on base and asked if we had really done what he had heard about. He was

incredulous. After landing, the deadheading crew had quickly exited the

airplane

out the left crew entrance door and boarded the bus without seeing the

right

wing.

The aircraft commander flying on this mission was our group commander. He

was

strong leader and an experienced pilot, physically active, a man's man who

played

handball several times a week and took on all comers. He was in command!

After

the short trip up from Dover AFB, barely over fifty miles, we were

receiving

vectors for a GCA approach to runway six. The weather forecast had not

changed

from the weather briefing we had received at Dover. We expected a ceiling

five

hundred feet and visibility two miles as I recall. There were thunderstorms

forecast in the area so we were anxious to complete the approach with

minimum

amount of vectoring.

As we settled in on final approach the Precision Approach controller became

a

"broken record" of "on centerline--on glide path." At about 400 feet the

runway

was clearly visible. We continued a normal approach and moments later the

controller suddenly switched from his repetitive on glide slope to

"aircraft-too-low-for-safe-approach-runway-not-in-sight-go-around." At the

same

instant everything in the windshield turned white. I suppose we had the

landing

lights on at that point.

When the aircraft commander hesitated, I took the aircraft, executing a

very

abrupt go-around. I remember thinking that I may have gotten the stick

shaker

during the initial go-around and days later I realized that it could have

been

the trees brushing the ailerons. As we climbed up a few hundred feet, the

aircraft commander looked down, saw the runway and said "There's the

runway,

let's land." "No sir! We're going around." I was not in command but was an

IP

and

did not think he would overrule me. I heard the navigator say something

about,

"I

think we touched down." I thought that was an inappropriate remark as it

might

demean the group commander's flying skills. In reality his altimeter was

right

on

because we later found out we had descended almost to the approach lights.

I had

thought I was looking down at what turned out to be a large light mounted

in the

center of an approach stanchion. In reality, I was probably looking

straight

ahead at that light with the aircraft paralleling the ground at about

twenty

feet

and several hundred feet short of the runway.

We went into holding and were soon joined by a commercial charter flight.

He had

not attempted a landing but was sent straight into holding. After about an

hour

the charter flight landed on the opposite runway. In hind sight I suppose

we

were

shaken by the go around because I remember taking some comfort in the fact

that

an aircraft had landed safely before us.

After parking the aircraft I was in the right seat completing paper work

when

the

scanner tried to talk to me over the long cord on interphone. His voice was

badly

broken and all he could seem to get out was a broken "s-s-sir." I finally

said

"scanner, what's wrong." All that came back was "Sir, you better look out

here

at

the right wing." I slid the chair forward and leaned toward the window.

What I

saw caused the strength to leave my legs. I sat there realizing that the

one

thing that I was not going to do was try to stand up.

After alerting the command post over the radio and requesting flying safety

to

come to the aircraft I finally decided I had the strength back in my legs

and

went out to survey the damage. As luck would have it we were in the spot

closest

to the light poles so we had a clear view of the damage. Another stroke of

luck

was that the wing was receiving an Operational Readiness Inspection and the

MAC

IG team was there to view the show. The wing safety officer was

disappointed in

my statement since I had no idea what had happened and we had considered

the

flight unremarkable until we saw the damage.

That was very early in the morning and the next significant event I

remember was

a visit to the approach control facility the next day. The OIC said that we

could

listen to the tape but that he could not release a copy. I made a personal

recording of the tape as everyone in the squadron was anxious for the

details.

Interestingly I heard tower transmissions that amazed me. Two C-141s had

landed

earlier and I heard the tower on the tape telling them both to "Taxi with

extreme

caution- aircraft not visible from the tower." This made sense as we had

experienced zero visibility prior to the go-around.

Although a full blown accident investigation was conducted by 21st Air

Force,

the

Airlift Wing was able to classify it as an incident based on the cost of

repairs.

Lessons Learned. At that time the Air Force, as well as most other aviation

experts knew very little about Wind Shear. It took the Eastern 66 accident

at

JFK

in 1975 to widen the interest in this phenomena. At that time the

investigation

team knew there was something called wind shear and asked questions which

would

make no sense at this time.

Having all of the information and knowledge at hand today leads to a

somewhat

obvious conclusion. I continued to fly in air transportation and received

extensive training in wind shear until 2003, when I retired from the FAA.

The

approach controller testified that our airspeed on final approach was 195

kts.

He

said he thought we were an F-105 which the Air Guard was flying at McGuire

in

1973. The accident board did not believe that we could have been configured

at

that speed even though the flight data recorder showed the flaps coming

down.

There was zero wind on the surface with a thick fog. Given what could have

been

at least a fifty knot tail wind, the pilot probably had the throttles near

idle

to maintain glide path. I did not have my hand on the throttles so I can

not

verify this theory. However, when the tail wind stopped at low altitude the

aircraft would have sunk dramatically, which it indeed did, after the high

speed

momentum bled off.

It would be wrong not to bring current knowledge of wind shear to this

flight

and

the ensuing investigation. Although the aircraft commander has died, his

flying

skills were called into question. I have a quote below from a wind shear

expert

which would certainly have challenged opinions at the time.

"In 1973 and before, the final cause of many accidents induced by wind

shear

were

labeled as pilot error. For perhaps the first time, the final report of the

Eastern 66 accident stated that the wind shear condition at JFK on that day

exceeded the capability of the aircraft and pilot for any possible

recovery.

Therefore perhaps for the first time in the history of aviation wind shear

was

listed as the cause of the accident vice pilot error."

John Attebury

Added, March, 2017 - From Jerry Carroll:

I was reminiscing about an incident back in the 70's when a C-141 I was

deadheading in back to McGuire AFB as a passenger got so low on approach that it

took

the tops off some (not very tall) New Jersey pine trees. At this point, it seems

almost like a dream in

a way.

Today I was searching around to see if there were any records of the incident,

and I came across the

C141-Heaven site. Amazingly, there I found a recounting of the story.

In those days, I was a C-141 aircraft commander, captain, based at McGuire, and

we had dropped our plane

at Dover and were hitching a ride to get home.

In John Attebury's comments, second paragraph, I am the aircraft commander who

saw him at the base the

Monday following the accident, when I was at the squadron turning in my

paperwork for my own recently

completed Europe trip. And yes, I was incredulous.

During the flight, as I sat in the back with my crew mates (the cockpit was

fully

occupied, as I recall)

I pulled on my headset to listen in on the cockpit chatter. Unfortunately, I

could not hear any outside

radio - only intercom. As I remember, there was very little or no talk, except I

do remember someone

saying 'Go around', and the plane starting to climb. It felt like a very normal

go around.

I didn't feel anything odd, no contact or anything, and nobody sitting with me

did either. No one in the

cockpit expressed any concern or seemed to have any idea we were in any kind of

danger. There was no

conversation about it at all - just routine cockpit talk as we climbed out and

came around for a

(successful) second approach and landing.

After we landed, Ops sent out two crew busses, and, after thanking the crew for

the ride, my crew jumped

onto the first one, parked off the left wing of the aircraft, opposite the wing

with the tree section,

and headed off to our squadron and home. It was late, it was raining, we'd been

gone for a week or more,

we were tired, and we were ready to get home. The next day was a Sunday, and we

could get some rest.

I was astonished when, that following Monday, the first thing I was asked when I

walked into the

squadron was if I had heard about the C-141 that almost bought it.

No indeed, I had not - tell me all about it.

It didn't take me long to realize that that was my flight they were talking

about, and we were all very,

very lucky to be alive!

After reading John Attebury's retelling of the episode, my foremost thought is

'Thank you, John. You

saved my life and every one else's on that plane when you took the controls and

went around. I did not

know that part of the story until I read your comments just now."

Amazingly, the disaster that doesn't happen becomes with the passage of just an

ever fainter memory and

tall tale. I've had a long and great life, and despite having had a few other

close calls during the

course of it, I'm still here. But that particular flight on that miserable night

was no doubt the

closest I've ever come to not being here.

And we didn't even know it!

Jerry Carroll

On 18 September 1979 this aircraft was involved in an incident that resulted in the destruction of the aircraft. It is recounted below.

The aircraft was on a local training mission. After several touch and go's, the

crew noticed that the "Brakes Released" light did not come on after the gear was

extended. The Dash-1, at the time, stated only that the crew should be careful

when applying normal brakes. The crew flew a normal approach and landing. After

touchdown, the spoilers opened only partly then closed. Only #4 Thrust Reverser

would deploy. Normal brakes were inoperative.

The instructor pilot attempted to control the aircraft and directed the copilot

to select Emergency Brakes. The copilot did so and then continued to make

multiple attempts to deploy the spoilers, depleting the #3 Hydraulic System

pressure.

With 4000 feet of runway remaining, the crew heard a loud bang. An electrical

malfunction within the gear handle caused the nose gear to retract. The aircraft

came to a stop 820 feet from the end of the runway and the crew evacuated. Fire

consumed the aircraft.

The actual malfunction was a short circuit within the Landing Gear Handle Relay.

This caused the touchdown relay to stay in the flight mode, and gave the nose

gear an up signal.

Emergency Brakes failed when #3 Hydraulic System lost pressure due to the

copilot's multiple attempts to deploy the spoilers. The thrust reversers did not

deploy because they were locked out by the Touchdown Relay, which was still in

the Flight Mode.

The deployment of the #4 thrust reverser was a malfunction, without which the

aircraft would likely have departed the end of the runway.

The crew escaped without injury, but the aircraft was consumed by fire.

The above information was provided by Paul Hansen

Source:AF Photo

The following are additional USAF photos and a few taken by George Miller. I've

included some notes that George wrote on the back of one of the photos here.

"647

was dismantled and parts returned to the Lockheed factory. The fuselage was sent

to the 78th Military Aerial Port Sqdn at Richards-Gebauer AFB , Missouri (Near

Kansas City) to be used as a loading mockup. The fuselage was cut into sections

and flown by army helicopter to the nearby Charleston water ports, where the

three sections were put aboard trailer trucks. The tail section was dropped (see

photo below for damage) and could not be used for the 78th purposes as the petal

door is needed for a training aid. There are also a few pictures of the wing and

tail on railroad cars before they left the base.

It appears this is in the hanger following the fire.

Probably being stripped of anything useful before being

dismantled. This was a scan of a negative that had a big thumb-print

on it. I couldn't get it to go away so take it for what it is!

Before it was dismantled into sections.

I can't be sure, but I suspect the field to the right of the

fence is where the photo below (of the chopper lifting a part

of the fuselage) was taken.

Tail is on a rail-car and ready to go.

Notice the radome in the lower right corner of this photo as well.

The tail of the chopper in this photo was covered

with a sticky label...it damaged the print.

Whoops. This part of the tail was dropped from the chopper.

Too bad we have no photo of THAT!

Wings on a rail car, ready to roll.

Notice that the flat-bed car appears to have been modified to

accommodate the wing shape near the front of the car.

Tail loaded.

In February, 2012, I got a note from Dario Dryden, who works down at the boneyard. He spotted this:

For some reason, it has survived all the of C-141 carnage, though I can't imagine why. Perhaps it's spring cleaning time at DM.